When observing a timepiece or jewellery, the fine details naturally attract the attention. Curiosity and fascination make you want to enter the world of the Lilliputians. A completely different story is told by the wheels, settings and scratches, but in order to hear the whispers of the tales, you need to be really close. Changing perspectives, approaching and distancing myself allows me to absorb the entire meaning of the piece – those the creator intended to convey and others that live perhaps only in my imagination.

A few days ago, one of my “All-Star” stops in Vienna, the Museum of Albertina invited bloggers and online magazines to play just the opposite: discover the stories the zillions of carefully composed colourful pixels tell when you zoom out from them. Pointillist artists, including Seurat, Signac and contemporaries occupied the walls of the Museum from 16 September.

10111001011010001

The 21st century poses new challenges for traditional institutes, such as Museums. Digital has become a major part of our lives and no doubt it is an ever accelerating trend. If the average attention span is a vanishing 8 seconds (according to Microsoft’s study [PDF] in 2015), how will a museum make an impact within such a short space of time? Can the museum reach out to people? Converse with the individual? Establish long-standing relationships? Or connect people based on their cultural interests? Can art flow on different online and offline channels with the ultimate goal of attracting people into the halls to discover the unrepeatable masterpieces in their complete beauty?

The experience within the museum is not the same either as it was before. Interactivity, walking back and forth through the frontiers of online and offline elements, and arousing emotions have become key success factors in capturing the visitor’s attention.

“Emotion-driven museum experiences will not merely present the facts but will provide opportunities and stimulate visitors to engage proactively in the world around them” – Future Of Museums: Social Impact + UX + Phygital.

Albertina, with one of the most important graphic art collections in the world and one of Europe’s largest private collections of classical modernist paintings, has placed strong focus to re-defining itself along these lines. They have an “online art collection” and actively engage with art lovers on social channels, too. The #AskACurator initiative on Twitter lets anyone to direct questions at the curators of exhibitions. And for the first time, Albertina opened a major exhibition with a dedicated press conference and tour just for online journalists.

Pointillism

There are movements in the history of art, which strongly influence artists throughout decades or even centuries. Pointillism, a painting technique whereby small and distinct coloured dots build up the image, is certainly one of them. Although being at its heights in the late 19th century, graffiti artists, tattoo artist (tattoos are essentially “pointilism”, typically using numerous needles at once to create lines) and graphic designers let themselves be inspired by the Pointillists’ style even today. Damien Hirst, one of the most famous and divisive artists of our time, has an extensive series of Spot Paintings. Inspired for sure, but the “Row”, the “Agaricin” or the “Zomepirac” are not exactly what the Pointillism essentially is…

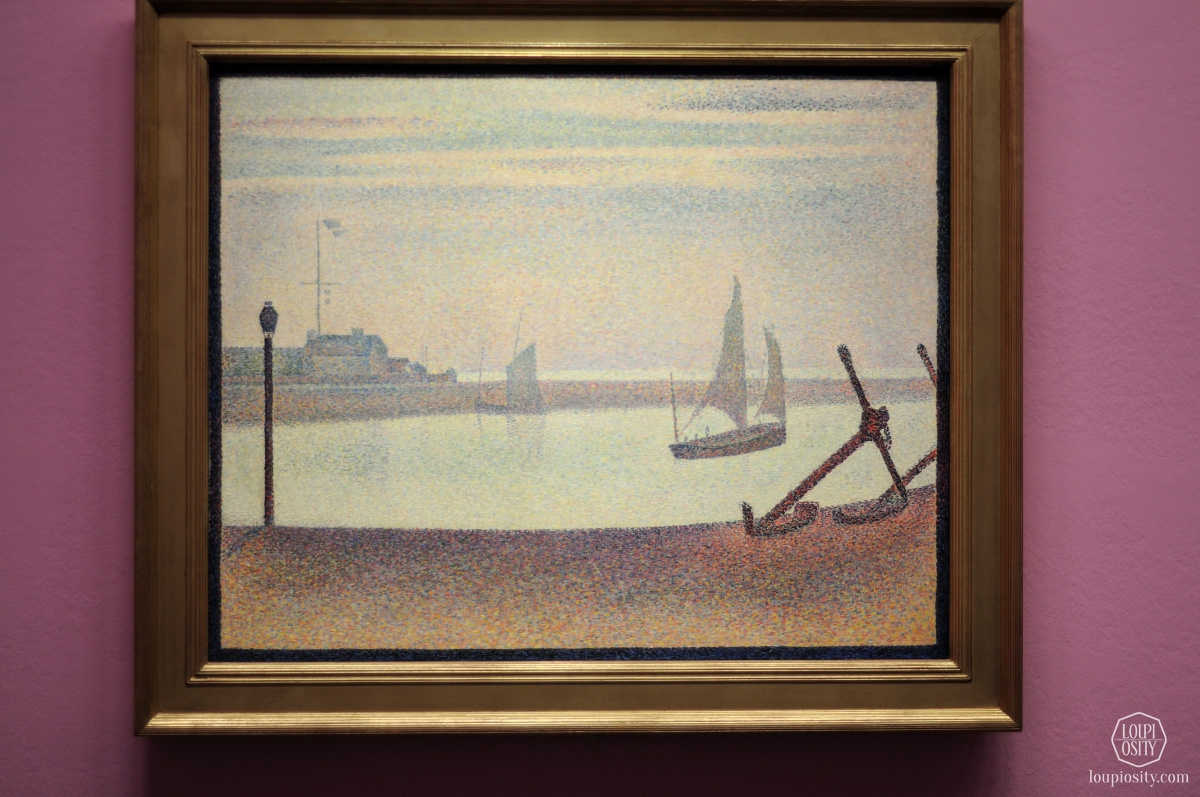

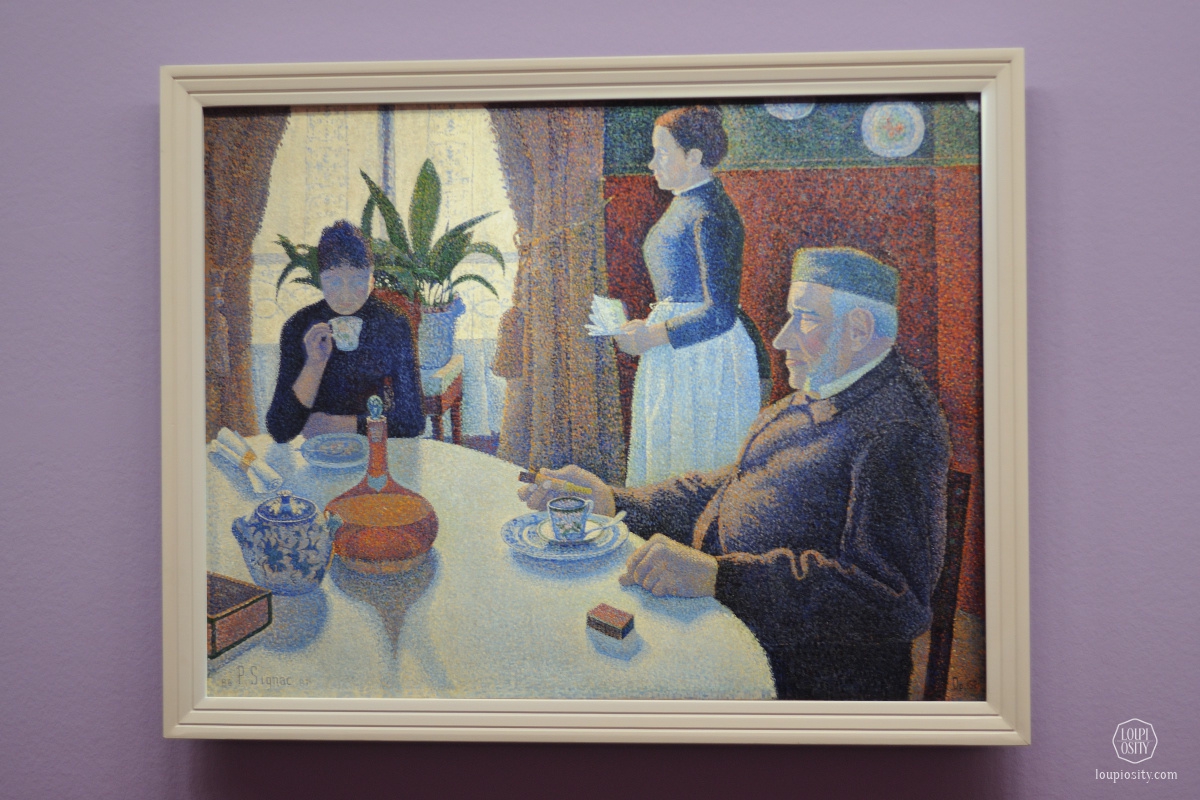

George Seurat (French painter, draftsman 1859 – 1891) and Paul Signac (French painter 1863 – 1935) are probably the most notable figures of Pointillism. Both artists experimented with the technique earlier, but A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte by Seurat and The Milliners by Signac presented in the Eighth Impressionist Exhibition in 1886 were the first, most pronounced artworks in this style.

Impressionism, a very important art movement developed in Paris in the 1860s by the founding members including Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Camille Pissarro, caused an “art-shock” with its loosened brushwork and lightened palettes of pure, intense colours. At the end of 19th century, new Post-Impressionist movements emerged. Pointillism and Divisionism also shocked with their new perception of colours, shapes and perspectives. Unsurprisingly, the first Pointillist works presented to the public received mixed receptions. The painting technique was new, the result was eye-catching but not necessarily easy to “digest” as the pictures were created dot by dot in order to shape a larger image.

Messengers of Pointillism

Although Georges Seurat lived only 31 years, he is one of the icons of late 19th-century painting. His colour theory discoveries became the foundations of the Pointillist technique. He studied the colour star of Charles Blanc and the works of French chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. He was known – among others – for his colour principles and the so called simultaneous contrast, which refers to the manner in which the colours of two different objects affect each other. Seurat interpreted these theories on exciting paintings.

He wrote to his friend Maurice Beaubourg (French writer, author of symbolists tale) in 1890: “Art is Harmony. Harmony is the analogy of the contrary and of similar elements of tone, of colour and of line. In tone, lighter against darker. In colour, the complementary, red-green, orange-blue, yellow-violet. In line, those that form a right-angle. The frame is in a harmony that opposes those of the tones, colours and lines of the picture, these aspects are considered according to their dominance and under the influence of light, in gay, calm or sad combinations”.

Paul Signac was among the founders of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, with the goal to “allow artists to present their works to public judgement with complete freedom”. He was Seurat’s friend and supporter and helped him develop Pointillism. His favourite themes were the French coast, the landscapes created by myriads of small, mosaic-like colour squares. Signac assigned an “opus number” to some of his paintings, he borrowed it from the world of music (in musical composition, the opus number is the “work number” of a composition).

An important figure of Impressionism was the Danish-French painter, Camille Pissarro (1830-1903). After many great Impressionist paintings, he began to explore new themes and methods and between 1885 and 1890 he turned to Pointillism. He was an avid advocate of Seurat and Signac. His great-grandson, Joachim Pissarro called him “the only artist who went from Impressionism to Neo-Impressionism”. What is even more interesting is that he abandoned Pointillism and in his final year returned to Impressionism.

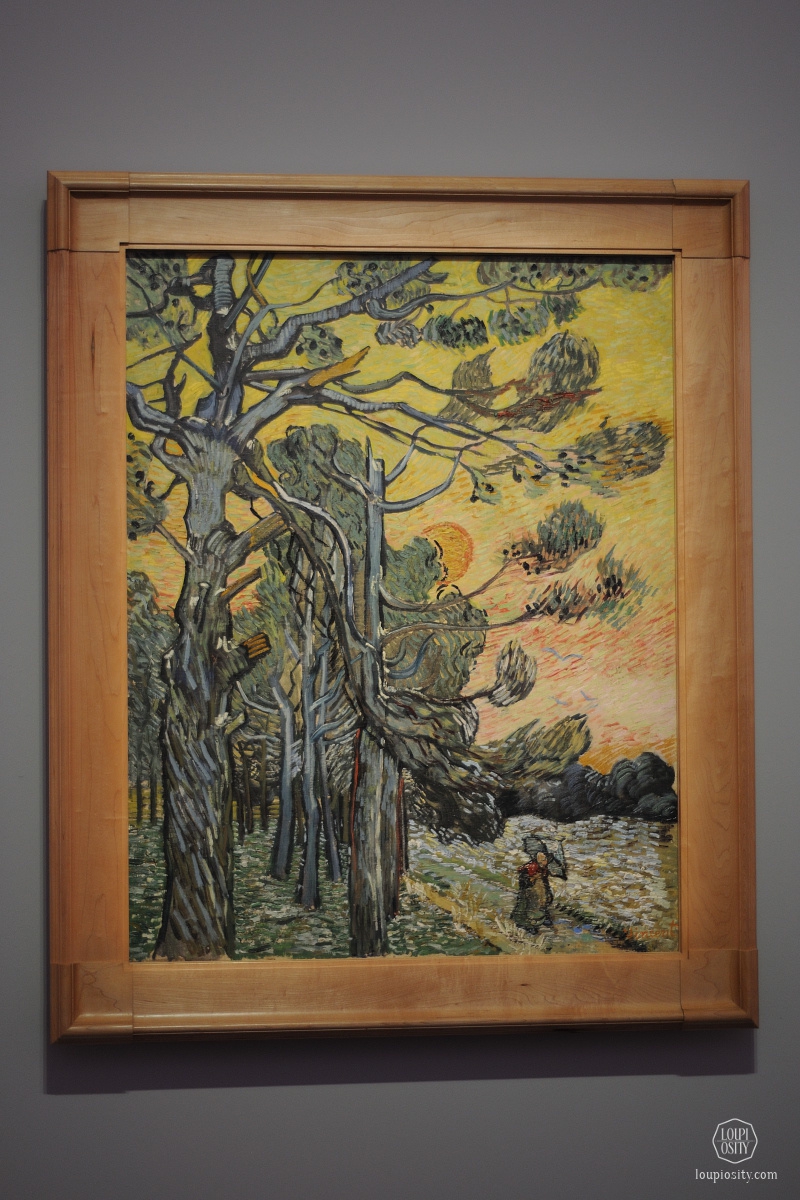

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) is among the most famous artists of the Netherlands with a short and troubled life but iconic artworks. These are characterised by bold colours, and dramatic, impulsive and highly expressive brushwork and he also adopted elements of Pointillism. He only briefly followed Pointillism, as he – similarly to Pissarro – had an aversion to rules. He declared, “paint what you observe and feel”. His works highly reflected his moods and affections.

About the “Pine trees at Sunset” (1889) he wrote to her sister, Willemien:

“ … it’s the one with the ravaged pines against a red, orange, yellow sky – yesterday it was very fresh – pure, dazzling tones – well while writing to you I don’t know what thoughts came to me, and upon looking at my canvas I told myself, that’s not it. So I took a colour that appears as matt, dirty white on the palette, which one obtains by mixing white, green and a little carmine, I slashed this green tone all over the sky, and there you are, from a distance it softens the tones by breaking them up. And yet it would seem that one spoils and dirties the canvas.”

One of the most influential artists throughout the second phase of Post-Impressionism was a French painter and printmaker Henri-Edmond Cross (1856-1910). He created paintings in many styles: with the dark colours of Realism, later Impressionism, he had Divisionist works and he also played an important role in shaping the second phase of the Neo-Impressionist movement. His legacy had a special impact on the artistic development of others.

Théo van Rysselberghe (1862-1926) was a Belgian Neo-Impressionist painter and the founder of Les Vingt (The Twenty), a Belgian group of modern artists. His three trips to Morocco inspired him to explore more exotic directions. He discovered the Pointillist idea in Paris and started to follow this style, even going as far as to “import” it to Belgium. However, he moved to Paris in 1897 and joined to Signac, Pissarro and others not only in terms of art, but also anarchism as a political view.

Pointillism had a great influence on Post-Impressionism, Fauvism and Cubism. Henri Matisse was one of the leaders of the Fauve movement in France. He combined the pure colours of Pointillism with wild expression, like the “Parrot Tulips” (1905) which he painted as a tribute to Henri-Edmond Cross.

With these artworks waiting for you at Albertina, it is time to point to a suitable day in your calendar between 16 September 2016 and 8 January 2017 and visit the museum. Points will form the image, and the images will probably reform how the world appears to you. Who knows? Tell me how you liked it.

Photo credits: Fruzsina Jelen for Loupiosity.com.

The photos were taken at the online press event at Albertina. All images used for illustrative purposes only. All registered trademarks are property of their respective owners.

All rights reserved.