Here I am holding a timepiece bearing the name of Ferdinand Berthoud. We are dating in a building which was erected at the heights of Berthoud’s fame according to the plans of his contemporary, John Sanders. The Duke of York’s Headquarters gives home today to the famous Saatchi Gallery, the scene of the annual watch exhibition, SalonQP.

Curiously enough, the stories of the building and the chronometers of Ferdinand Berthoud intertwine. They were born at the time of colonization give and take between the Dutch, English and French, and thus were brought alive to satisfy military needs. The building was originally the Royal Military Asylum for school children of soldiers’ widows and later the Duke of York’s Royal Military School. The development of chronometers was largely fuelled by the naval race among European empires competing for land and resources. Although the latitude had been calculated reasonably accurately by observing the angle of the sun and stars, up until the 1750s the reference was missing to judge the ships’ East-West position on open waters. And although since 1530 this reference was suggested by the Dutch scientist Gemma Frisius to be the time on a known fixed location, which compared to that in the ship’s actual position enables the determination of the exact longitude, no one before the British John Harrison was able to build a chronometer reliable on the sea to measure the reference time. So Harrison’s H4 “Sea Watch” has had an extreme importance, although he had to walk through the mill to receive the prize announced by the Board of Longitude for the invention.

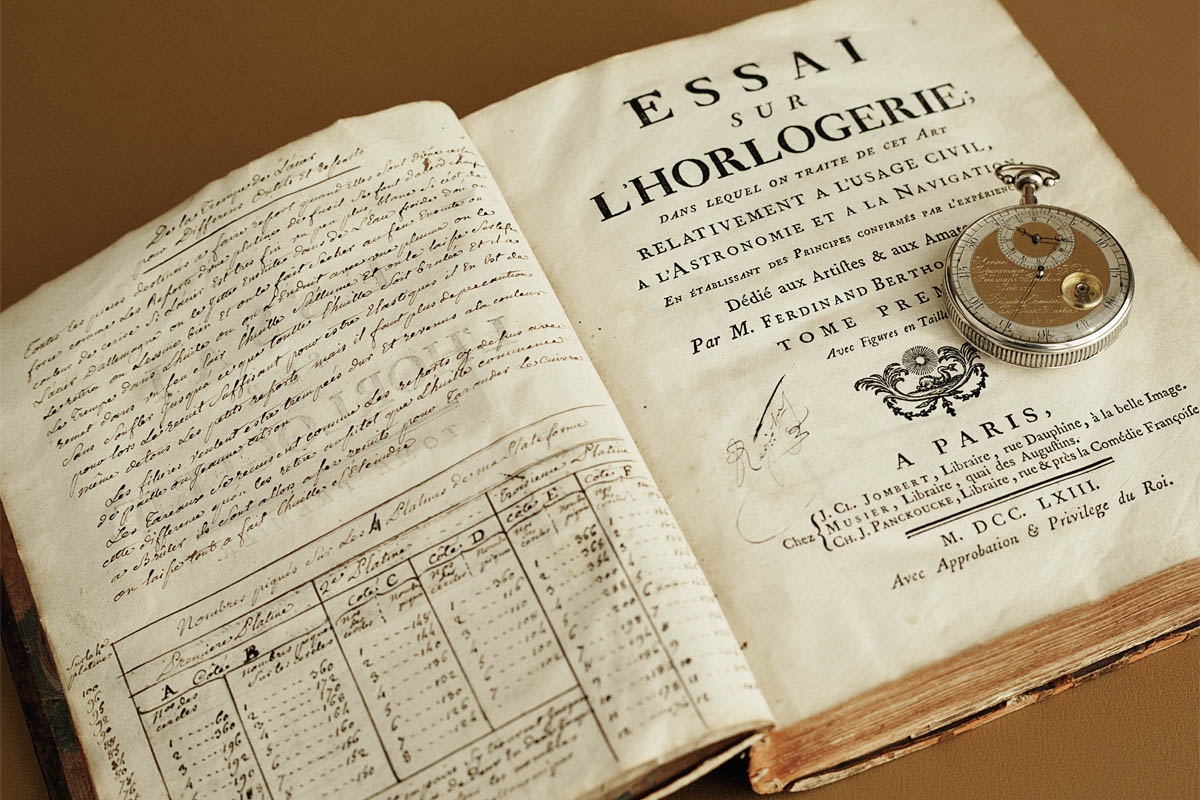

At around the same time few hundred kilometres away in Paris, Ferdinand Berthoud, the Neuchâtel canton-born clockmaker was active in designing equation clocks. These register the time of an actual solar day, which differs from the arbitrary 24 hours we commonly use. In 1752 his invention was mentioned in the “Machines ou inventions” approved by the Académie, and this allowed him to join the highly restrictive Paris guild. Afterwards he turned his attention to marine chronometers and with the support of King Louis XV, Berthoud travelled twice to London to study Harrison’s pieces. In a race with fellow Parisian watchmaker Pierre Le Roy he made several marine chronometers, such as the N° 6 and N° 8, and became an appointed Clockmaker to the French Navy and later to the King in 1770. In 1773, he received the commission to produce four units per year and to supervise all marine clocks created for the French Admiralty. Through decades of active clock-making he documented designs, experiments and conclusions, and his repertoire included articles about the equation of time and solar cycle measuring clocks in Denis Diderot’s and Le Rond d’Alembert famous Encyclopédie. He also published an Essay on Horology about the civil use of these instruments.

Chronométrie Ferdinand Berthoud

Less from a localization and more from a social positioning perspective mechanical chronometers are popular even today. The Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres is kept busy by watchmaking brands to certify the outstanding time measurement abilities of their pieces. What is a nice feat and sign of quality today, meant the difference between life and death at sea a few hundred years ago and thus chronometer attributes do give a special flavour to contemporary mechanical timepieces.

As said, I was holding a recently announced Ferdinand Berthoud piece at SalonQP. It is the love-child of Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, Co-President of Chopard, who besides running the fine-watchmaking leg of Chopard does have in his portfolio several decent undertakings fuelled by pure love. For instance, Mr. Scheufele always takes part in Mille Miglia, not missing an opportunity to joyride his veteran rollers. Or obtaining the rights for the name Ferdinand Berthoud in order to create a small boutique brand with a few exceptional mechanical pieces – to be a tribute to the master watchmaker as he puts it. These seem to contribute to his self-realization and serve more as sources of joy than income, and I have a feeling that although it would be great to sell out the pieces and make money with it, profitability this time is less important than enjoyment.

Although the new brand is a member of the Chopard Group, it is separated from Chopard’s facilities and production lines. Ferdinand Berthoud employs a handful of watchmakers who design and build the strictly limited models in Fleurier. The first chronometer that came out of their workshop is called FB1, which although being a wristwatch, bears attributes so characteristic to the marine chronometers of Berthoud’s age.

The first and most conspicuous mark is the octagonal case, which in spite of the 44mm diameter and the 1,120 watch components is very neat. It can be ordered in two precious metals: white and rose gold. The angular case contains 4 sapphire windows on the sides and a large opening on the back, providing a fantastic view of the calibre FB-T.FC.

The movement sits in a container and incorporates solutions rarely seen in today’s wristwatches. The structure of the calibre follows the pillar-type architecture of 18th century marine chronometers and if you flip the device, three main units catch the eye immediately: a tourbillon at 6 o’clock and two drums on the top, one being the mainspring barrel and the other a fusée. The barrel and the fusée are linked by a chain (474 steel links and more than 316 pins, so it takes a considerable time to assemble) and the old mechanism ensures constant torque for the gears. When wound up, the chain is coiled around the fusée cone. As the mechanism runs, the chain in unwound from the fusée’s narrow end and goes on the barrel. The weaker torque of the mainspring is compensated by the larger radius of the fusée ensuring a constant driving force.

The power reserve can also be seen on a cool device directly linked to the barrel. As the barrel rotates it moves a little cone up and down, the run of which is followed by a feeler-spindle connected to the indicator hand.

The regulator is a 3Hz tourbillon, which drives the second hand fitted unusually to a wheel identical to the tourbillon carriage.

The timepiece was born from love and will end up on the wrists of fellow fanatic lovers. The entire construction is unusual yet smart. To tell the truth the watch does not have a popular model figure but has a lot of personality, which kind of codes that it will only end up on collectors who can live it up to it.

Photo credits: Ferdinand Berthoud, Loupiosity.com.

All registered trademarks are property of their respective owners.

All rights reserved.